Black and minority ethnic (BAME) employees face routine discrimination by an “institutionally racist old boys network” running some of Britain’s largest companies and are 90 per cent less likely to land a boardroom job than white, middle-class applicants, a new study has concluded. Contributor Anuranjita Kumar, the Managing Director and Head of HR – Hubs – RBS,

Independent research by the global human resources director at the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), suggests that BAME candidates stand only an eight per cent chance of promotion to chief executive (CEO), chief financial officer (CFO) and other senior director roles as a result of racial prejudice and nepotism that remains “rife” in the UK and international workplaces.

BAME applicants, however capable, were found to be consistently overlooked because their cultures and religious beliefs are seen to be at odds with most company’s “private members’ club mentality”.

Existing board members want “likeminded” individuals to join their ranks and rarely consider anyone whose views, way of life or upbringing could be different from their own. White applicants are almost always favoured by recruitment panels because there is a “sense of comfort” in employing people who look, act and think like they do.

The research was conducted by Anuranjita Kumar, the Managing Director and Head of HR – Hubs at RBS, who has been listed as one of the world’s leading female HR practitioners by Fortune India.

Her conclusions are based on more than 600 hours of conversations and meetings with over 500 male and female BAME professionals, including 125 from the UK, who she has privately mentored on race-related matters, cultural integration and top-tier promotion.

All reported feeling that their “face didn’t fit” despite giving good interviews and possessing the prerequisite qualifications and experience for the boardroom or director role they applied for.

Of these, three-quarters described the recruitment panel – typically made up of existing board members – as an “old boy’s network” and the promotion process they experienced as “institutionally racist and biased against people of colour”.

Just four per cent of those BAME applicants she interviewed were successful, and all reported that they felt obliged to adopt western mannerisms and to tone down their natural accents during the interview.

This, she says, is despite UK corporations having “ramped-up” their efforts towards greater diversity through measures such as revised policy frameworks and company-wide sensitivity training.

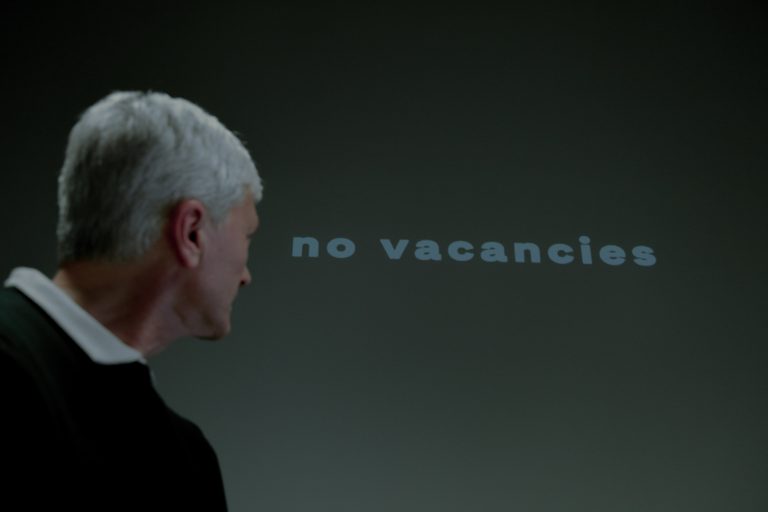

The findings were revealed for the first time this week at the launch of Kumar’s new book, Colour Matters? The Truth That No One Wants To See, which is published by Bloomsbury India.

Speaking at a launch event in London, she said BAME individuals in Britain and elsewhere continue to face “antiquated prejudice” at the hands of the “white elite”.

Kumar, the former Head of HR at Citi Bank, South Asia, said: “Global organisations today thrive on close-knit and diverse teams.

“Yet, having interviewed and coached hundreds of people from multi-ethnic, multi-professional backgrounds from across the world, there can be little doubt that much of the global workplace remains entrenched in institutional racism.

“BAME professionals are faced not only with antiquated prejudice but also with the challenges of understanding the invisible rules and codes that are self-evident to the majority but unfamiliar to a new or different society.

“In the workplace, this places those BAME applicants looking for top-tier promotion at a distinct disadvantage because they fail to chime with the private member’s club mentality of many large British and international boardrooms.

“It is clear that recruitment panels, and the inevitable wealthy white elite they comprise, are looking solely for likeminded people – there is a sense of comfort, albeit a deeply flawed one, in that way of thinking.”

Kumar, whose research was conducted independently of RBS, added: “Based on the feedback of those people I have spoken to and mentored, and taking existing studies into account, I believe strongly that BAME individuals – whether male or female – are at least 90 per cent less likely to be selected for a top-tier role than white applicants.”

In 2017, the UK’s biggest companies were given four years to appoint one board director from an ethnic minority background as part of a package of measures outlined in a government-backed review into the lack of diversity at the top of corporate Britain.

The target is voluntary, but companies that fail to comply will have to explain why.

But last October, a progress report found that the number of FTSE 100 company directors from ethnic minority backgrounds had declined.

Just 84 of the 1,048 director positions in the 100 biggest companies on the London Stock Exchange were held by a business leader from an ethnic minority, down from 85 in 2017.

According to reports, the majority of FTSE 100 boardrooms had no ethnic diversity, whilst 54 of the 100 firms did not have a single board director from an ethnic minority background.

Kumar, warned that organisations which fail to diversify voluntarily are at risk of becoming “irrelevant” in today’s multicultural society.

She said: “In every society, people must learn to embrace differences and connect with those of other races. By working together, for instance within a corporate setting, people can come to value diversity for the wider world-views and global perspectives it can bring, appreciating the strength of unity and the mutual benefits it confers.

“Those companies that judge employees on the colour of their skin and not as human beings are stuck in a time-warp and will, without exception, become irrelevant in the modern marketplace over coming years.

“Whether they like it or not, the world is changing and companies that fail to adapt and embrace multicultural, progressive change are likely to wither and die.”