The world of work has changed

Where recruitment boards once advertised vacancies strictly labelled as either full time or part time and permanent or temporary, along with details of the location you’d be working from, prospective employees of the post covid era now find a plethora of filter options available to them; flexitime, hybrid, fully remote, work from anywhere, #WorkTogetherWednesdays and many more.

However, contention around hybrid working remains; research by Towergate Health & Protection suggests that 98% of employers have implemented measures to persuade employees back to the workplace, while Microsoft reports that 51% of UK hybrid workers would consider leaving their company if flexible working wasn’t available.

One of the organisational impacts of hybrid working has been a reduced commitment to rituals and routines (e.g. coming in every day) that acted as the fabric or glue that held organisations together. Beyond their social value, these rituals play a key role in enabling coordination and collaboration. Outdated or ill thought-through approaches have the opposite effect – and can even have a net negative effect on performance and engagement:

“I resent travelling to the office to only spend 30 mins of the day actually interacting face to face with my colleagues. The ones who are not there have either not been expected to show up, or have not been willing or able to travel in.”

Hybrid working has become a lightning rod for a range of issues in organisations, and designing a coherent and accepted approach is complex, often sparking cultural conflicts across generations, gender, and race.

Meanwhile, the matrix, where employees report to multiple leaders, remains the most common organisational structure for medium to large organisations[1]. Boards and CEOs continue to ask whether they have the right operating model to deliver on their goals, and in most cases the answers they come up with are a variation on the matrix that was already in place.

While on paper these structures seem eminently pragmatic and practical, they often have bad press due to fears about lack of clarity and/or autonomy; concerns around navigating multiple reporting relationships; and negative experiences of working in poorly implemented matrix structures. Much of this is linked to the high levels of coordination that matrix structures require. We can all point to examples where a particularly tricky issue is finally resolved through a well-handled conversation, as trust is finally built between individuals and teams. While this can be done online, impromptu face to face interactions often play a part.

Matrix structures combined with hybrid working practices run the risk of damaging the relational fabric of an organisation, impacting employees’ ability to get things done at pace. A key task of leaders and managers therefore becomes to ensure that the relational fabric is not only maintained but strengthened. Put simply, that there is enough coordination in place both to deliver performance and create a sense of belonging.

Strengthening the relational fabric

- Designing drumbeats

Thinking deliberately about the right organisational drumbeat can be a helpful way of getting the best out of both matrix and hybrid working.

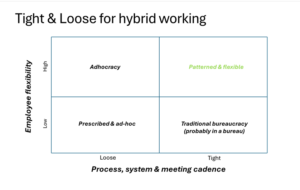

While a combination of decreased individual flexibility and tight processes and systems runs the risk of feeling bureaucratic, high levels of flexibility and a loose set of processes and systems often feels ad-hoc and inefficient.

In order to strike an effective balance, Lynda Gratton[2], suggests a “patterned and flexible” approach, which offers employees flexibility supported by tight processes and systems and regular meetings. This fosters a sense of belonging and inclusion in hybrid teams, as well as enabling them to be productive. In order to reap the benefits of this approach, decisions around processes, systems and meeting cadence need to be taken at a divisional or enterprise level, rather than fully devolved to individuals or teams.

A practical example is seen in hybrid organisations with designated on-site team days, creating weekly cadence that supports coordination and makes explicit the organisational benefit of physical presence.

Regular, structured interactions are also essential to help maintain team cohesion and feelings of inclusion, regardless of physical location. This includes regular check-ins and team days, transparent communication channels, and inclusive decision-making processes (where appropriate), and requires much more deliberate thought in a hybrid and matrix world than in mostly co-located set up. What’s important is that the interactions are designed to deliberately improve connectedness and create space for conversation, rather than traditional top-down broadcast formats.

Leaders and line managers have an essential role in designing and facilitating these touch points, as well as bringing to life the rationale for the choices around cadence and drumbeats

- Creating a culture of quarterly contracting

Matrix organisations, by definition, require individuals to hold organisational tensions and polarities: market customisation vs. global standard, short term pricing decisions vs longer term value proposition etc. This only works if the individuals in question have enough shared context and have agreed a framework for decision making. Without this, organisational tensions rapidly become personal and can turn into turf wars around the business of the day.

Leaders and managers therefore need to put ongoing, deliberate attention into role definitions, decision making, and alignment between individuals and teams. This requires explicit regular conversations around what each party needs from the other, and how they experience the process of working together.

Ultimately the conversations need to be had by individuals, and it needs to be seen as the expected and default thing to do, rather than something that is at the discretion of individuals. Creating an organisational framework and process which becomes part of the culture to support is critical. Leaders doing it and role modelling is essential- but not sufficient.

The following five question framework is a useful starting point:

- How have we experienced working together over the last quarter?

- What has worked well and not so well?

- What are our respective key priorities for the next quarter?

- What do we need from each other in the next quarter?

- What changes – if any- do we need to make to how we work together in the next quarter?

These questions and approaches set up an adult-to-adult conversation and can be used between line managers and team members, and between individuals from different teams. They can help resolve potential tensions in an agile and localised manner, rather than through escalation and policy changes.

However, individuals cannot create these conversations without system level support. There is a role for digital assistants to prompt here – a potential example of AI helping the humans to be human.

- Holding the line: firm but not rigid

Most leaders and line managers grapple with how to exercise authority and make decisions in a world where things are increasingly contested.

You might make decisions about flexible working but how do you manage it in practice? You might arrange senior team touch points for decision making but how do you decide who to include or exclude? How do you judge what meets a standard and what falls short?

Ensuring that the underlying rationale is available means that leaders can be transparent with their teams and use their judgement to handle challenges.

The notion of “firm but not rigid” is helpful here, not least to help make the distinction between an exception to a rule and undermining intent. For example, recognising the difference between team days to support coordination and a blanket requirement for presence between certain hours; or the difference between key team touch points and expanding meeting invites for the sake of sharing information or inclusion.

Being able to stay firm on decisions within reason is essential. What’s more, line managers must have the ability to hold effective and robust conversations about performance and working patterns, both virtually and face to face. This may well require some investment and expectation setting, as well as regular calibrating within the leadership community.

Avoiding defensiveness is key

We increasingly understand humans as social creatures who need to feel significant, competent, and liked, and it is perhaps no accident that the concept of psychological safety is felt to be so important at the moment. Without this, defensiveness becomes the norm, with negative consequences on performance and well-being [3]. Individuals can find themselves clinging to the masts in the stormy seas of matrix and hybrid organisations.

However, good organisational drumbeats which create a sense of belonging, regular conversations that allow for connection and appreciation, and understandable frameworks can mean people are not just weathering the storm. Rather they are actually enjoying working in matrix and hybrid organisations.

[1] Research commissioned by McKinsey (2016) found that 84% of employees who responded worked in a matrixed structure

[2] organisational theorist and Professor of Management Practice at London Business School

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vjSTNv4gyMM